Like many patients with a spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, Patty was diagnosed with many things—and underwent some needless procedures—before finally receiving the correct diagnosis and treatment.

Patty has always been incredibly active. Even now, at 75, she exercises on a near-daily basis, doing yoga, Pilates, barre workouts, and more. Her leak symptoms began after a jet-ski accident when she was 71. She came away from the accident with sciatic nerve pain, headaches, extreme fatigue, and a feeling in her ears she could only describe as a kind of persistent fullness. After months of living with those symptoms, her ENT physician recommended a mastoidectomy, a kind of ear surgery, but the surgery ended up doing nothing to improve her symptoms. Her headaches and fatigue were so severe, she had to nap and lie down most of the day to function, and whenever she was upright for more than a half-hour at a time, the head pain was unbearable.

After this discovery, Patty had spinal imaging done (a CT myelogram of her spine), but—like up to half of patients with spinal CSF leak—her leak was not visible. A non-targeted lumbar epidural blood patch offered only temporary relief.

With her spinal imaging negative and her head and ear pain persisting, another ENT, suspecting Patty might be suffering from a cranial CSF leak (a CSF leak in her head), recommended a second ear surgery. But that surgery conferred no benefit and revealed that the leak was definitively not in her ear. Ultimately, after several more tests and epidural blood patches yielding little in the way of results, Patty went to a center with a team of experts in treating spinal CSF

This time, the doctors were able to see her leak. Her leak was a type of spinal CSF leak called a CSF-venous fistula—an abnormal channel between the space where cerebrospinal fluid is and a vein outside the dura mater. What this meant was that Patty’s cerebrospinal fluid was being siphoned off through a rogue vein. No matter how much cerebrospinal fluid she produced, that fluid was constantly being whisked away into her circulatory system instead of kept inside the dura mater, where it normally is.

This type of leak often requires surgery to address. After her previous unnecessary ear surgeries, Patty was anxious about whether or not this procedure would work for her. But it did. Her recovery was slow, and complicated with rebound high intracranial pressure—having too much fluid around her brain and spinal cord instead of too little—and she was frustrated by the physical limitations it required. But within a year, she was back living her very active life, making art, and doing her favorite “boot camp” exercise classes.

Patty is thankful to have her normal activity level back, and her advice for anyone suffering from a spinal CSF leak is to not be shy: Push for what you need, and advocate for yourself. “There is hope on the other side,” Patty says. “It’s tough to go through what you go through, but what you learn about yourself is so important.”

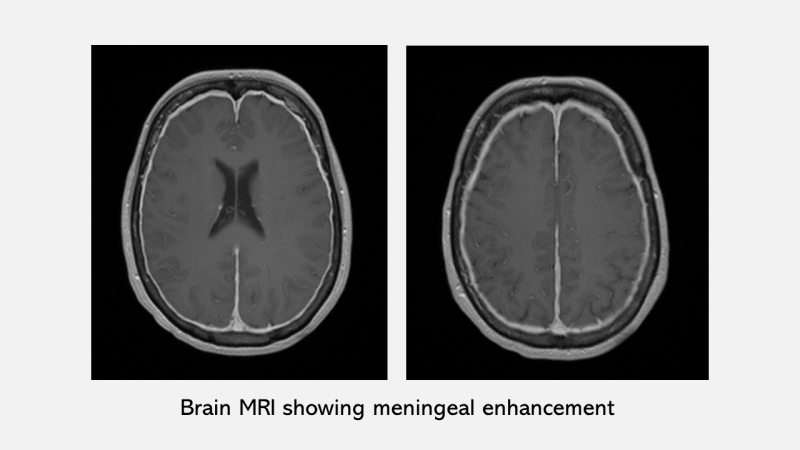

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension is causally associated with CSF leaks at the level of the spine and NOT with spontaneous CSF leaks in the head. This remains a common diagnostic error due to low level of familiarity among physicians and other health professionals. It can lead to inappropriate diagnostic testing and surgeries, directed at the level of the skull base instead of along the spine, as it did in Patty’s case, despite her brain imaging being diagnostic of intracranial hypotension.

The sensitivity of spinal imaging is such that spinal CSF leaks may not be evident. Occasionally, with repeated imaging, an elusive leak may be located. The CSF-venous fistula type of leak is a type of leak that was first recognized in 2013 and requires some expertise with imaging to visualize.

We hope that Patty’s story not only demonstrates her remarkable