Treatment

Treatment for spinal CSF leak

Treatment for spinal CSF leak varies from conservative measures to surgical procedures. Some patients have symptoms that resolve spontaneously in a matter of hours, days, or weeks without ever seeking or requiring medical care. However, some serious complications such as stupor/coma or large subdural hematomas dictate emergent and more aggressive intervention. A substantial percentage of patients respond favorably to one or more epidural blood patching procedures. When epidural blood patching is unsuccessful or if symptoms recur, spinal imaging findings help to guide further treatment. Epidural patching with fibrin sealant may be directed at a known or suspected leak location, or a surgical repair may be the best option. Surgical repairs of spinal CSF leaks have good success rates in the hands of experienced neurosurgeons, but a subset of patients have persistent symptoms and associated disability.

Conservative: Symptom Management

A conservative approach to treating spinal CSF leak involves managing symptoms as they arise.

For general symptoms:

bedrest / horizontal positioning

oral and IV hydration (temporary symptomatic benefit)

oral and IV caffeine (temporary symptomatic benefit)

oral theophylline (questionable benefit)

steroids (questionable benefit + risks significant = rarely recommended)

use of abdominal binder

For nausea:

ginger products and/or medication such as ondansetron (Zofran)

For pain:

non-opiate analgesics (limited effectiveness)

opiate analgesics (regular use not supported by pain management guidelines)

complementary approaches: nutrition, supplements, mind-body techniques, acupuncture

Epidural Blood Patch (EBP)

In an epidural blood patch, the patient’s own blood is injected into the epidural space (the space just outside the dura within the spinal canal), forming a “patch” over the dura. This is most often done by an anesthesiologist or a radiologist, using fluoroscopic guidance and intravenous sedation.

An EBP can be directed (that is, placed at the known location where a patient is leaking, such as a post LP leak) or it can be non-directed (placed at lumbar or thoracolumbar locations). A non-directed EBP is usually performed when a leak site has not yet been localized, or for diagnostic purposes. The volume (the amount of the patient’s own blood administered) ranges from small (10 mL) to large (100 mL).

The precise manner in which an EBP is helpful is not entirely clear, since patching remote from actual leak location is often helpful. A favorable response to an epidural blood patch supports the diagnosis of a leak but often lacks durability.

While restrictions after an EBP are individualized, it is typical for physicians to recommend avoidance of bending, lifting, twisting, and straining (valsalva) for about 4-6 weeks.

Typical radiology suite where an EBP might be performed. Reproduced with permission from Wouter I. Schievink, MD

Epidural patch with fibrin glue sealant

Fibrin glue sealant is a biologic adhesive, comprised of a pooled blood product that has been treated with a two-step process to reduce the risk of viral transmission. Fibrin glue sealant can occasionally result in allergic or anaphylactic reactions, but pre-treatment with medication reduces that risk. Injection of fibrin sealant into the epidural space is an “off-label” use, but accumulated experience has demonstrated this to be safe in experienced hands. This procedure is most often performed by neuroradiologists with imaging guidance and intravenous sedation to target specific known or suspected leak locations. Anesthesiologists and other clinicians also perform this procedure. It may be used in isolation or in combination with whole blood.

Repairing a spinal CSF leak with surgery

The findings and interpretation of spinal imaging is of critical importance in surgical planning and outcomes. Surgical repairs are often less technically straightforward than might be anticipated, due to frequently noted abnormal dura and the variety of anatomic leak types and locations. The specific approach is tailored to the type and location of the leak and to the individual patient.

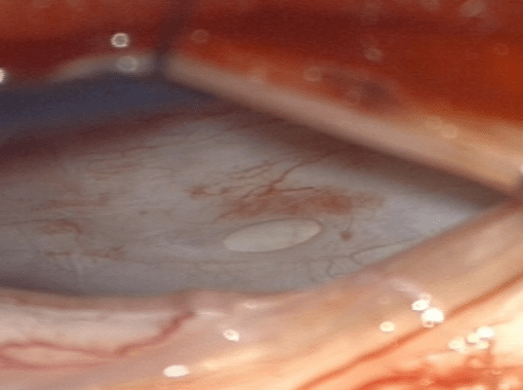

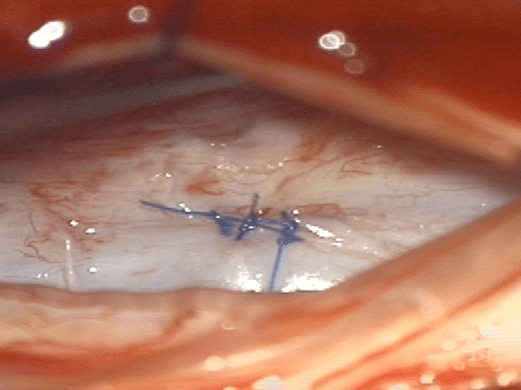

These operating room photos show a ventral or anterior (meaning, “front”) dural defect before and after suturing to repair. This repair was done with a posterior (meaning “behind”) approach, gently moving the spinal cord to access the defect.

Dural defect before suturing

Dural defect repaired (Reproduced with permission from Wouter I. Schievink, MD and Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, CA.)

Non-repair surgical procedures

When other measures have failed, some procedures have been used in carefully selected patients to reduce the severity of symptoms, such as epidural saline infusions via indwelling epidural catheter, or lumbar dural reduction surgery.