Unlike most patients, who endure months or even years of misdiagnosis and unnecessary medications and testing, Mason benefitted from the quick-thinking actions of his long-time personal physician.

Mason was 53 when his headache started. He had always been incredibly active, traveling and playing sports from hockey and golf to tennis and volleyball, and had never experienced anything like it. Headaches were rare for him, and this particular headache even more so. It arrived seemingly out of nowhere; it improved when he lay down and get worse when he stood up; and, even more strangely, it persisted, day after day. He managed for a while with over-the-counter medications, but nothing seemed to help.

Mason was 53 when his headache started. He had always been incredibly active, traveling and playing sports from hockey and golf to tennis and volleyball, and had never experienced anything like it. Headaches were rare for him, and this particular headache even more so. It arrived seemingly out of nowhere; it improved when he lay down and get worse when he stood up; and, even more strangely, it persisted, day after day. He managed for a while with over-the-counter medications, but nothing seemed to help.

Mason went to see his long-time family doctor for an annual physical and mentioned the strange headache he’d been having. His doctor, having had Mason as a patient for some 25 years, recognized Mason’s complaint of this sudden and terrible headache as unusual for him. Rather than suggesting migraine or some other cause for the headache, the doctor sent Mason straight to the emergency department.

Mason came away from the ED with a diagnosis of a pinched nerve and a prescription for muscle relaxants and pain pills, but Mason’s family doctor thought that was neither a reasonable explanation for, nor a solution to, his symptoms. He had Mason admitted to a hospital for further evaluation. After three days of testing, including a CT scan and several MRIs, the doctors could find nothing to explain what could be causing Mason’s headache. It was recommended that Mason have a lumbar puncture, but that, too, came back as inconclusive. The neurosurgeon who was brought in to consult told Mason that he was unable to provide a definitive diagnosis and the best he could offer was a diagnosis of exclusion—a diagnosis of a medical condition reached by a process of elimination—which in this case was idiopathic pachymeningitis, a thickening of either the intracranial or spinal dura mater, evident on his brain MRI. But neither the neurosurgeon nor Mason’s family doctor was confident in that diagnosis.

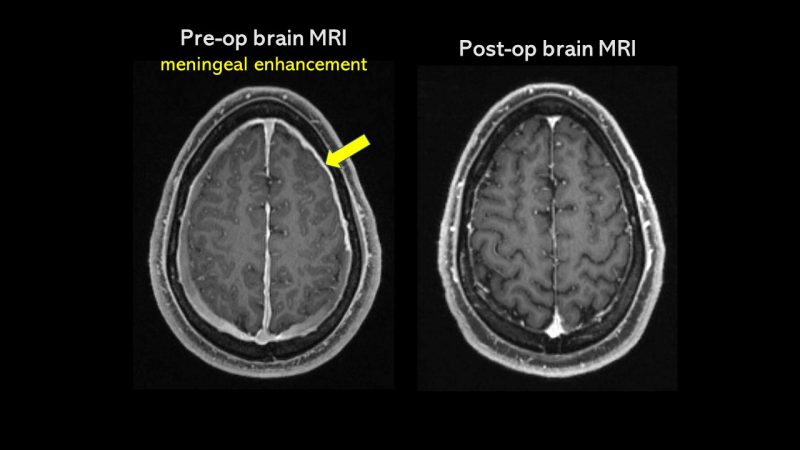

Mason was referred to another neurosurgeon, who reviewed Mason’s history and ordered more testing. But this time, the doctor suspected a much more definitive diagnosis: Mason’s brain MRI showed evidence of meningeal enhancement, which is a sign of intracranial hypotension due to spinal CSF leak; he didn’t have pachymeningitis.

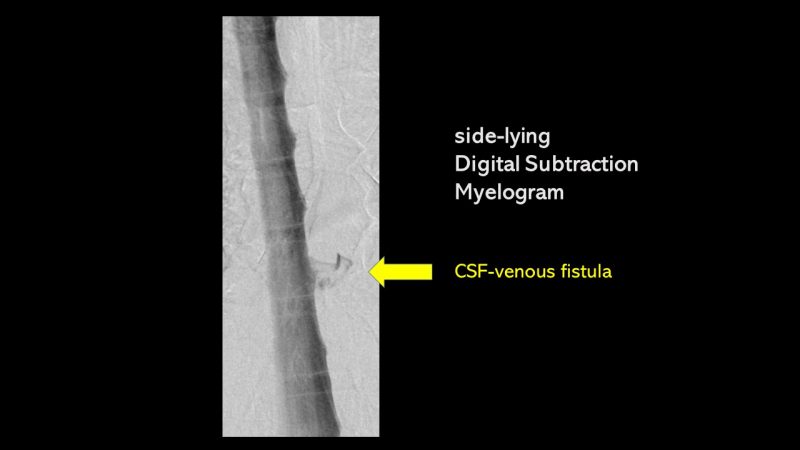

The specialist then ordered a digital subtraction myelogram (DSM), specialized imaging of the spine, performed with Mason lying on his side during the test. This time, the test was definitive: The imaging revealed a CSF-venous fistula.

A CSF-venous fistula is type of spinal CSF leak, an abnormal channel between the space where cerebrospinal fluid is and a vein outside the dura mater. What this meant was that instead of Mason’s cerebrospinal fluid being circulated along the brain and spine inside the dura mater, that fluid was being siphoned off through a vein. The lack of plentiful CSF surrounding the brain and spine within the dura mater was what was causing Mason’s headache.

Mason was quickly scheduled for surgery to repair the CSF-venous fistula, and the procedure was a success. His most prominent memory of the surgery is afterward when he realized the only pain he felt was at the incision site. His headache pain was totally gone.

During his recovery from the surgery, he had a few instances of rebound intracranial hypertension—a feeling of high pressure in his head—and the occasional headache from bending over or sitting. But overall his recovery was easy, manageable, and without complication. In fact, Mason felt so good that just a few weeks after, he pushed his doctor to clear him for sports again. After several months, Mason was indeed able to go back to playing sports, and just a few months after that, he was back to playing at full strength again.

Mason feels incredibly fortunate. Not only for the intervention of his family doctor, who likely saved him months of suffering but for the specialist who suspected a spinal CSF leak and pursued testing until he found it. He is also thankful that the surgery to repair it was, in his case, so straightforward and uncomplicated. Now he enjoys reaching out and connecting with other patients, and wants to contribute in any way he can to raise awareness about the disorder.

Our team at Spinal CSF Leak Foundation wishes to extend our appreciation to all those physicians working so hard to help patients, as well as those who assisted with this feature story.