Martha considers herself fortunate to have received a relatively speedy diagnosis and treatment—but it wasn’t an easy process.

Martha was on her way home from her son’s hockey tournament when she first noticed the headache. As a former nurse, she was mildly concerned, but over the next two weeks, the pain became so severe that she worried she might have a brain tumor or a brain bleed.

She went to the emergency room, but the staff there, unfamiliar with her symptoms, assumed she was a drug seeker, looking for pain relief. She had a CT scan, which was incorrectly interpreted as negative, and a lumbar puncture, which was incredibly painful, as it took the doctors a long time to be able to collect enough cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). They discharged her with an order for a brain MRI, scheduled for 2 weeks later.

After her experience in the ER, her symptoms became much worse. It was nearly impossible for her to function with so much pain and brain fog, and she found herself having to be horizontal most of the time. Martha continued her work as a clinical researcher, despite her pain and cognitive dysfunction. She took conference calls while lying down, and even traveled on a business trip, in an effort to carry on as if she was fine. But she wasn’t fine.

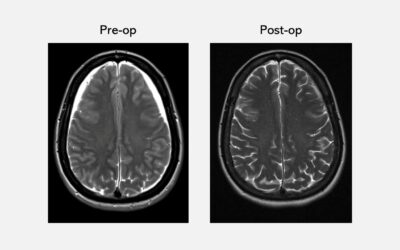

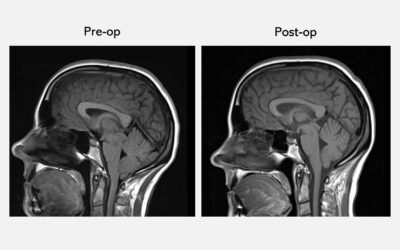

But once Martha underwent her brain MRI, her doctor told her she needed to be hospitalized immediately. Martha was understandably alarmed when she was told that she had a “brain bleed”: her brain MRI had revealed brain sag, as well as bleeding

She returned to the emergency room and had a non-targeted epidural blood patch, which gave her some relief. But a week after being sent home, her symptoms returned and she could no longer be upright. She returned to the hospital for another epidural blood patch, which failed to help her symptoms at all. She was then admitted to the hospital for three weeks. It took time for her to be transferred to a hospital capable of more specialized diagnostic testing, and so she spent Christmas and New Year’s in the hospital, waiting.

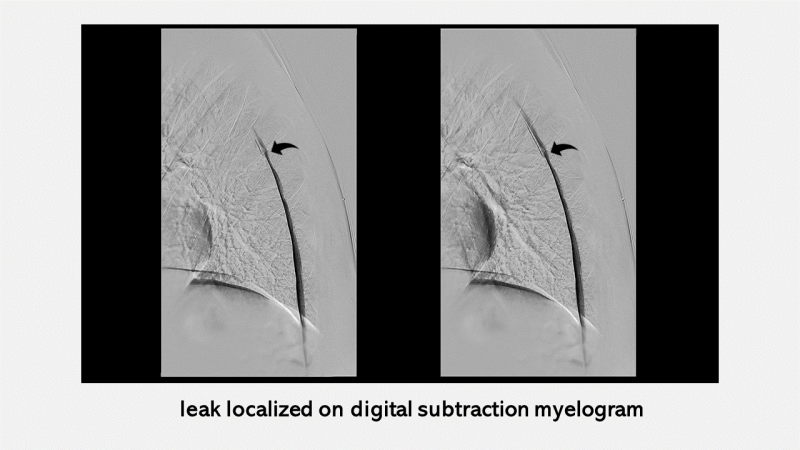

Finally, she was transferred to another hospital, where she had specialized type of spinal imaging called a digital subtraction myelogram (DSM). The DSM indicated that her leak was in front of her spinal cord, near a large bone spur. She also learned from her neuroradiologist that the original head CT she’d had in the emergency room was, in fact, not normal, and that, like her brain MRI, it indicated distinct brain sag. She was given a targeted epidural patch with fibrin sealant, which offered relief for three days while she was on bedrest, but the headache came back within a day of being upright. She found herself sicker than she ever had been. Bedridden, unable to read or watch television, she stared at the ceiling. “Those were dark days,” she says now of that time. “I was like a zombie. [That time] is all kind of a blur to me.” Her daughter, in her second year at college, and her son, a sophomore in high school, found it difficult to reconcile the energetic, hard-working mother they knew with the mom who was now bed-bound and struggling to get through the day.

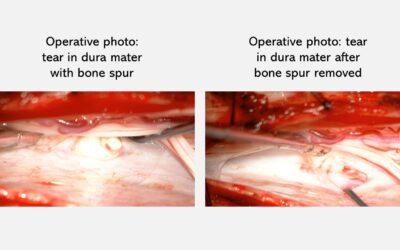

After the targeted patch failed, Martha was referred for surgery. In order to access her leak, which was in front of her spinal cord, her neurosurgeon had to carefully move the spinal cord slightly to one side. Then, the tear in her dura mater was able to be seen, along with a very large bone spur. The bone spur was removed first, followed by repair of the tear in the dura mater.

After the surgery, Martha’s back was sore, but her low-pressure headache was gone, never to return. Her recovery process was slow but sure: it took a long time to resolve the cognitive issues she

We at Spinal CSF Leak Foundation wish to extend our appreciation to the physicians who work so hard to help patients and who also assisted with this presentation of Martha’s story.