It’s not uncommon for patients to be disbelieved before eventually finding a proper diagnosis and effective treatment for spontaneous intracranial hypotension due to a spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. When Jack became ill at age 14, his parents pushed hard for his symptoms to be taken seriously. Here is Jack’s story

Jack had experienced migraine headaches from time to time as a young teen. So even at just 14 years old, Jack knew what to do when his head pain started. He was shooting hoops in backyard with a neighbor when the pain came over him, and so he stopped playing, went inside, took an analgesic, and laid down in a dark room for a while. But as the pain continued, leaving him curled up on the cool bathroom floor, heaving with nausea, he knew this was different than anything he’d experienced before. His mother Jody did what she often did when Jack had a headache, asking him to rate his pain on a scale of one to ten. His response—”a nine or ten”—alarmed her. And so off they went, to the emergency department of their local hospital.

There, he was treated for migraine headache and given IV fluids and migraine medication. After several hours, he returned home, hopeful that things would improve. But as the days passed, his pain increased. He couldn’t be upright without a terrifying headache, and his parents watched helplessly as their son, a star athlete, was confined to lying flat.

(A hallmark of the head pain experienced by people with spinal CSF leak is that it responds poorly to migraine medications. Read more about migraine and other misdiagnoses here.)

“You need to stop calling this a migraine”

A few days after that first trip to the emergency department, Jody and her husband Burke took Jack to a children’s hospital. Jack was evaluated by a neurologist and was given a CT scan.

“The CT scan set off a few alarm bells, because they were saying there was some evidence of some weird stuff going on,” Jack’s dad, Burke, says of that first hospital visit. “But it was not a direct path to getting answers.”

In fact, Jack’s primary diagnosis was still thought to be migraine. Jody and Burke were urged to look into possible migraine triggers, including allergies and other issues.

“We almost had his braces taken out,” Burke said, after brainstorming with Jack’s dentist and orthodontist as to whether his dental work could be a potential source of head pain.

Burke also wondered about whether Jack’s intensity as a star soccer player could have played a role. “He’s a very physical kid in soccer. And a couple weeks before this happened, he had a pretty bad fall from high up where he knocked the wind out of himself and couldn’t breathe for a little while.”

Eventually, they grew impatient with the migraine diagnosis. Jody remembers taking Jack to a neurology appointment and Jack being unable to stand up without throwing up from the pain. She told the neurologist, “You need to stop calling this a migraine. We know what a migraine is. This is not a migraine.”

An indirect path

Jack’s parents continued to push for answers. They reached out on social media, asking people for advice or insight into what could possibly be happening to their child. And they continued to push the doctors, as well—something that was not always welcome. Some of the physicians they met with even suggested that Jack’s parents were perhaps too invested: Could they be making their own son ill, causing or fabricating his symptoms? Or could this be psychosomatic, could it be that Jack simply enjoyed spending time at home, not going to school, and getting attention from his parents?

Jody and Burke knew this was not the case. They were concerned parents, and their son was suffering. Jack would much rather be out on the soccer field rather than stuck on the couch, and they would much rather he be his normal, healthy, active self.

As the weeks continued, Jack’s symptoms only grew in intensity, and he began to develop new issues in addition to his head pain—including a collection of symptoms that was diagnosed as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

POTS is a form of orthostatic intolerance that is associated with the presence of excessive tachycardia (fast heart rate) and many other symptoms upon standing. For Jack, this meant that every time he stood up, in addition to his head pain, his pulse would race to 200 beats per minute, as though he’d just run a sprint. Soon, the only time he felt symptom-free was when he was sleeping.

(More about POTS and spinal CSF leak: How POTS can be confused for spinal CSF leak or appear alongside it — Spinal CSF leak symptoms — Video: Kristen was treated for POTS before being correctly diagnosed with spinal CSF leak.)

A second misdiagnosis

Jack went back to the hospital and had more imaging done, as well as a spinal tap. It was so difficult for the physician to extract spinal fluid, they had to pause the procedure, give Jack IV fluids, and try it again. Still, they found so little spinal fluid, there was barely enough to take a sample. But instead of this pointing to a diagnosis of spinal CSF leak, Jack and his parents were told that what he had was viral meningitis.

By this time, Jody and Burke had talked to enough people online and read enough about Jack’s many symptoms to know that he did not have migraine or viral meningitis, and that he needed to be evaluated for spinal CSF leak.

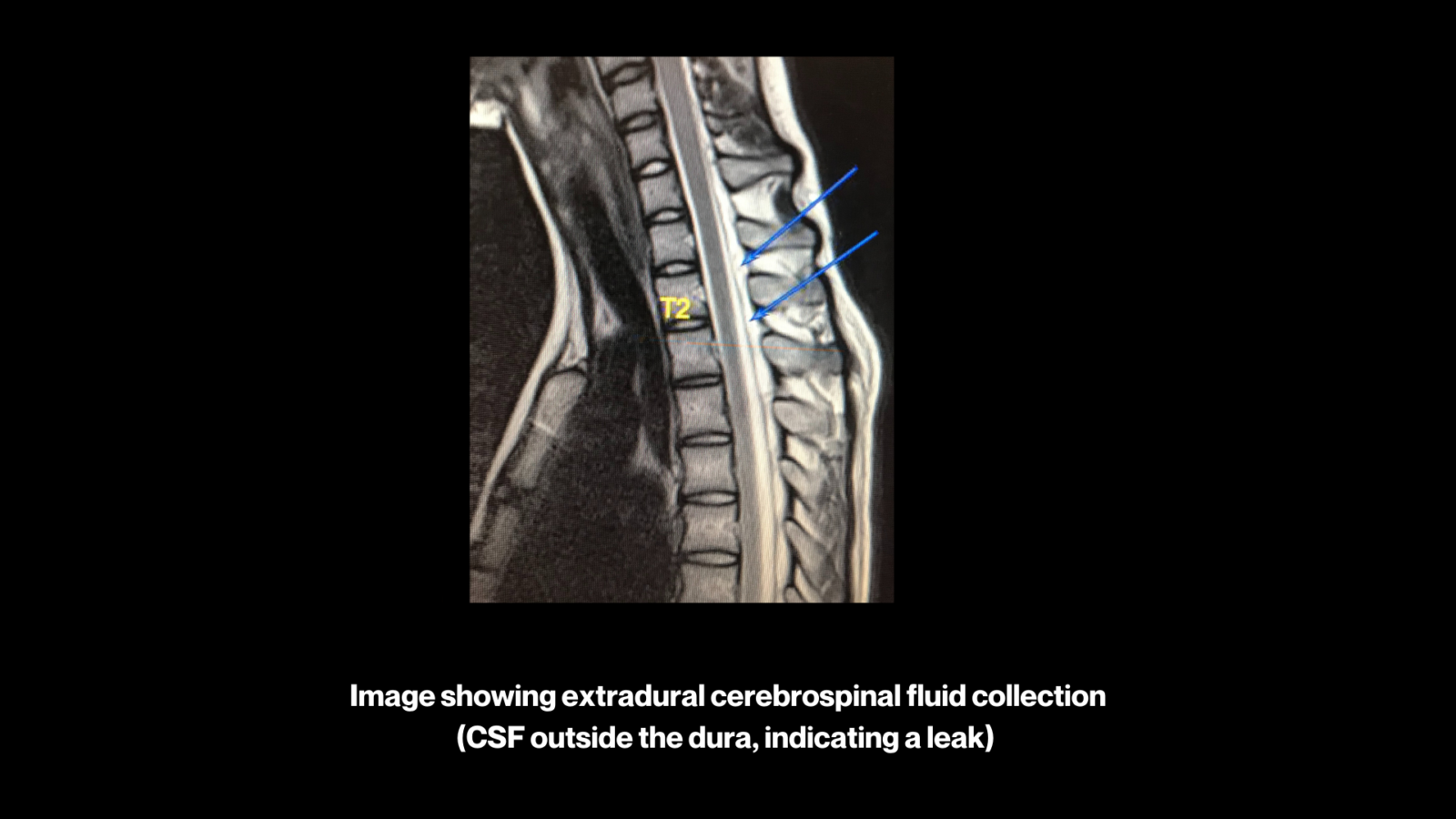

The brain and spinal cord are bathed in fluid known as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid is held inside layers of connective tissue called the meninges, which surround the brain and spinal cord. The outermost of these layers is the dura mater, normally a tough connective tissue. A spinal CSF leak happens when the spinal dura mater has a hole or tear, allowing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to leak out of this enclosed space. This results in intracranial hypotension, a low volume of CSF remaining around the brain and spinal cord—the cause of Jack’s debilitating symptoms.

A way forward

Ultimately, Jack’s doctors at the children’s hospital consulted with specialists from a center with more experience diagnosing and treating spinal CSF leak. And on his next MRI, his physicians were finally able to detect evidence of a leak.

Armed with this evidence, Jack’s parents sought a second opinion with a specialist far from their home, who reviewed all of Jack’s imaging and concurred. In fact, the specialist was able to spot clues as to Jack’s true diagnosis of spinal CSF leak on even the earliest of Jack’s brain images—clues the other doctors missed.

There are five findings typically seen on imaging that can be remembered by the mnemonic “SEEPS” when considering the diagnosis of spinal CSF leak. SEEPS stands for: Subdural fluid collections, Enhancement of pachymeninges, Engorgement of venous structures, Pituitary hyperemia, and Sagging of the brain. However, it is important to note that the absence of these findings does not rule out a spinal CSF leak. (Read more about spinal CSF leak diagnosis here.)

Finally, the proper treatment

At the specialist’s recommendation, Jack was given an epidural blood patch by a local anesthesiologist. In an epidural blood patch, the patient’s own blood is injected into the epidural space (the space just outside the dura within the spinal canal), forming a “patch” over the dura. This is most often done by an anesthesiologist or a radiologist, using fluoroscopic guidance and intravenous sedation. (Read more here about blood patching and other spinal CSF leak treatment.)

The anesthesiologist was concerned about doing an epidural blood patch high up in the spine, especially in a younger patient, so Jack was patched lower than the suspected site of the leak. After the procedure, he was placed in the Trendelenberg position—the bed tilted so that his feet were higher than his head—for about an hour, in the hopes that the blood would spread upwards along the spine.

As he returned home that night after the procedure, Jack remembers feeling disappointed. “I still basically had the same kind of headache, it just felt a little bit better.”

But then the next morning, he woke up early and was thrilled to discover that his head pain was completely gone.

A bright future

Once Jack got approval from his doctors to resume activity, he slowly started returning to school and sports. And not only did his head pain improve, his POTS symptoms improved as well. In just a few months, he was back on the soccer field, doing what he loved.

Of living with the uncertainty of an invisible illness and shifting diagnoses, Jack says, “I think learning to advocating for myself was definitely one of the most important things. And then patience is key throughout the whole process. Because if I wasn’t patient throughout the whole thing, I don’t know where I would be right now.”

Where he is right now: graduating from high school and heading off to college. As his dad put it, “It’s good to have this all in the rear-view mirror. Every now and then Jack will get a minor headache and we start to wonder if the spinal CSF leak is going to come back. But so far it’s just been a regular headache. Hopefully it just stays like that for the rest of his life.”

The team at Spinal CSF Leak Foundation extends our appreciation and thanks to the family, physicians, and staff who assisted with this feature story, and to all those working so hard to help patients and raise awareness.