Spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak is an under-diagnosed cause of disabling daily headache with other neurological symptoms and complications that can happen to anyone. The underlying problem is a hole or tear of the dura mater along the spine, the tough layer that normally holds the CSF in around the brain and spinal cord. A spinal CSF leak is treatable, BUT ONLY if the correct diagnosis is made. The tagline – because your dura maters℠ – highlights the TREATABLE aspect of this often very disabling neurological disorder.

Because spinal CSF leak is unfamiliar to most physicians, it is often misdiagnosed. Patients can suffer for months, years or decades with the wrong diagnosis and the wrong treatments. Medications rarely help. The most common symptom of headache is often much worse after minutes to hours of being upright, so patients may have difficulty functioning normally while upright. The degree of DISABILITY can range from mild to profound.

Our primary goal of Leak Week is to raise awareness so that more patients might be correctly diagnosed and treated. We interviewed Dr. Linda Gray-Leithe of Duke University Medical Center about intracranial hypotension due to spinal CSF leak.

Can you share with us some of your thoughts about why this diagnosis is often missed or delayed?

I think because there’s been, in general, a lack of education about the whole problem. People with spinal CSF leak can present in so many different ways. Patients don’t always have positional headaches. Sometimes, if it’s chronic, they just have a chronic daily headache without obvious postural aspect.

And then you can’t always see findings, such as sinking brain and dural enhancement, on brain MRI. In addition, physicians are not always well-versed in the imaging findings.

So, with normal imaging and a variety of different presentations, most doctors — general diagnostic radiologists, neurosurgeons, neurologists — they don’t think about CSF pressure. They just think “migraine.” Often, when people get diagnosed with migraine, that means that doctors stop thinking about other potential causes.

I had a patient who started having headaches in 2002 that lasted until 2006. She had a swollen pituitary gland, and a pituitary tumor was assumed to be the cause of her headaches. They just followed it — thankfully they didn’t biopsy — and she actually developed downward herniation of her brain and a big syrinx [fluid-filled cyst or cavity] of the spinal cord, and that’s what finally brought her to our attention: she had a surgeon who put in a shunt to drain the cyst in the spinal cord, and she got worse. He brought the imaging to neuroradiology and we recognized that this patient had intracranial hypotension and just needed a blood patch. And then she got completely better. It’s a lack of knowledge.

Neuroradiologists, in general, are familiar with the imaging findings, but general radiologists are less familiar. I can think of an example of a patient in whom the brain imaging studies were read by a general radiologist who saw one of the typical findings of a swollen pituitary gland and dural enhancement — but he didn’t put it together. He didn’t realize that’s intracranial hypotension. The patient later came to Duke, where the neurosurgeon who read the report was also unaware of intracranial hypotension findings on brain imaging. The patient ended up having a biopsy of the pituitary gland. The patient still had headaches and was sent to us for evaluation of possible base-of-skull CSF leak after the pituitary biopsy. We reviewed the imaging studies, which clearly showed classic findings of intracranial hypotension. The patient also had an obvious spinal CSF leak on CT myelography.

You and your colleagues at Duke see a lot of patients with intracranial hypotension. Do you have any sense or research on what percentage of patients are misdiagnosed before they see you or one of your colleagues?

Probably 85 percent. The level of knowledge is getting better, but slowly. It’s amazing — it’s like a big ship, it’s really hard to turn the trajectory.

There are now four neuroradiologists here at Duke who train physicians from other centers and speak at medical conferences. Patients come into the medical system in so many different directions because the presentation is so varied. So to impact diagnosis, we need to target many specialties, including radiology, neurology, neurosurgery, otolaryngology, even orthopedic surgery, because a lot of patients present with neck pain. Dental professionals also see patients who present with facial pain.

What are some of the incorrect diagnoses you see?

In addition to migraine, Chiari I malformation is a very common one. And then sinus disease — a lot of patients have face pain, which can be due to intracranial hypotension. A lot of people get diagnosed with occipital neuralgia, and doctors don’t really think or know about a different cause of pain in the back of the head. POTS [positional orthostatic tachycardia syndrome] — a lot of people with a diagnosis of POTS actually have intracranial hypotension. Patients with spinal CSF leak can have endocrine problems, too — diabetes insipidus, low cortisol or high prolactin or other hormone abnormalities. So, endocrinologists need to be educated too.

What are some of the complications you see?

If a doctor sees bilateral subdural hematomas in somebody who doesn’t have an explanation for that — such as being on anticoagulant medication or an absence of trauma — then the physician should absolutely be thinking about intracranial hypotension. Double vision, facial pain, blurry vision, even dementia are not uncommon. One patient that I saw recently developed dementia and headaches and his daughter went to 15 different neurologists with him because it just didn’t make sense to her. He’d be well for a couple of months, then he’d decline. It just didn’t seem to fit the pattern for Alzheimer’s. Fifteen different neurologists told her that she needed to accept the fact that her father had Alzheimer’s disease and she needed to put him in a nursing home. And he had a spinal CSF leak! We found it, we patched him; the patient is back to 100 percent. So, dementia and cognitive decline is a huge complication, I think.

Can you tell us a bit about the importance of brain MRI for patients suspected of having this disorder?

Brain MRI with contrast is super important because if you have the characteristic imaging findings, you know exactly what you’re dealing with. Then we can work to find where the problem is.

Would you share with us the range of spinal imaging techniques that your team uses to localize leaks for targeted treatment?

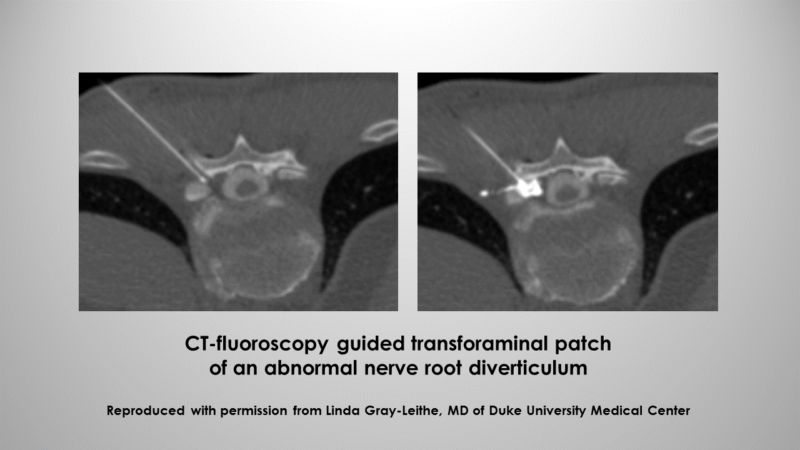

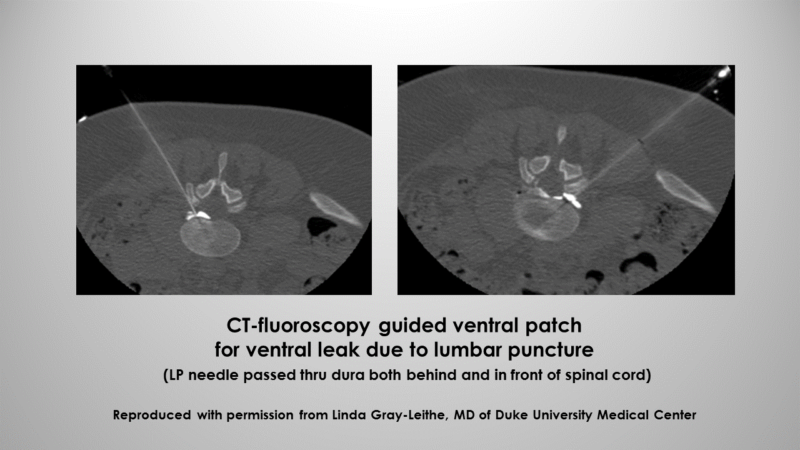

We use CT fluoroscopic guided imaging for our lumbar punctures and CT myelograms as well as for treatment with epidural patching. We can get an imaging study within about five minutes of putting in the contrast. We also do digital subtraction myelography — although not under general anesthesia. And then the other thing we can do is put in a needle under CT guidance and then put in the contrast and scan the patient back and forth several times looking for either a fast or a slow leak that way. That’s just a fast (or dynamic) CT myelography.

[CT-fluoroscopy is CT with the additional capability of real-time moving imaging called fluoroscopy, in order to help guide procedures in real-time in the CT scanner. When a needle is inserted, being able to see precisely where the needle is going as it is inserted adds precision and speed to the procedure. CT-guided procedures without fluoroscopy involve scanning, then moving the needle, then scanning, then moving the needle, which takes more time. Regular fluoroscopy is also used for guidance, but the image is flat, instead of a slice.]

MR myelography for CSF leaks can be a tool. It was through the use of MR myelography and increasing the pressure that I discovered that leaks can occur under discs intermittently and slowly, and also with arthritic facet joints. Now that I know that, I can guess that is the case with CT myelography when I don’t see the leak. When I don’t see an obvious leak now, because of my past experience with MR myelography, I look for the most likely potential site of leak, often a calcified disc. MR myelography has also helped in several cases when I can’t find the leak and there are too many possible sites.

I think in general, nuclear medicine imaging has almost zero role in picking up spinal CSF leaks.

Can you explain non-targeted versus targeted patching and when each is usually used?

Generally, I use non-targeted patching when I don’t see a leak and am not sure if low volume is actually the problem. If I know that low volume is the problem and want to improve the patient’s condition quickly, that might be an indication to do a non-targeted patch. A non-targeted patch might also be considered prior to sending the patient to a facility where the appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment can be performed.

Targeted patching guided with CT-fluoroscopy is my treatment of choice when the site of the leak is known precisely or approximately. In the setting of no obvious leak, I would look for the most likely potential site of a leak, target that site, and then follow the patient for improvement of symptoms. Hypothetically, if this site is under a calcified disc, I would patch that spot at least twice, and if the patient’s symptoms improved for at least several weeks, but then the patient relapsed, I would send the patient for surgical evaluation and definitive treatment.

Orientation: top = back of patient, bottom = front of patient

Orientation: top = back of patient, bottom = front of patient

Would you describe how you approach a patient in whom a leak is suspected but does not show up on imaging?

When I have a patient whose images don’t show an obvious CSF leak, then I look for the most likely potential site of leak and I target that. Or, if we really think, based on symptoms, that the patient likely has a CSF leak, we can do a non-targeted blood patch and see if they respond to that.

When I don’t see a leak, I also consider CSF venous fistula. [CSF venous fistula can be more challenging to see on CT myelography]

Another thing to think about is cervical degenerative changes, which can also cause a positional headache. Or sometimes it is high pressure — high-pressure patients can present with positional headaches. Knowing the opening pressure might give us an indication of that.

We may pursue additional imaging as well, such as an MR myelogram.

Do you have a sense of the percentage of patients that you see with confirmed or suspected leaks that are cured?

Thankfully we are all getting smarter about this problem, the diagnostics, and the treatments. I have worked with some patients for 8-10 years now and it has been a journey for all of us. It is tough to give an accurate percentage as the denominator is such an unknown. More and more patients are getting better and can get better if they are correctly diagnosed. Of all the patients I have treated, I would say I have 10-15% who are not yet completely sealed and healed. Sometimes this takes work and dedication to the patient. I have had some patients who just had to wait until the diagnostics improved and the treatment options caught up with the problem.

What do you see as the top research priorities that may improve outcomes for more patients?

Right now, we have a research project going on at Duke that is a placebo-controlled trial of saline vs. blood and/or fibrin glue patching.

Number two would have to be comparing targeted versus non-targeted blood patches.

We need some better tools in order to actually target the places we want to get to. We need better tools for actually doing ventral [in front of the spinal cord] patches.

If we could have a tool where we could take off these little pieces of disc percutaneously, without having to send the person to surgery, that would be super fabulous. So, if we could develop more minimally invasive ways of treating the problem so people don’t have to go to the operating room, that would be great.

We also need some better medications and better ways to treat the rebound high pressure that occurs after a patch.

Do you have any additional thoughts that you would like to share?

We need more education for medical providers. You know, I think a lot of people are just so unfamiliar with the problem, physicians, in general, are just so unfamiliar with the problem, and they think it’s a neurology or a headache specialist problem; but in point of fact, spinal CSF leak touches so many different medical subspecialties that every doctor should be thinking about it when they see a patient.

We need a training program so that we can train more CT-interventionalists who are well-versed in the problem so that they can go out into other states and start taking care of patients as well. Every headache center across the country should have the capability to work up this problem themselves. They should have people who trained to do the diagnostics and implement treatment.

It’s also really important to listen to patients. The way we even figured out about rebound high pressure here at Duke is that I would patch people and they’d say, “I’ve got a headache again, but it’s different,” and so I’d say, “Let’s figure out what’s going on.” So then I’d put a needle in people’s backs and realize their pressure was much higher, and I’d take off fluid and they’d get better, and so then I knew, okay, what I’m seeing here is rebound high pressure after a patch. And then I started working with drugs to lower the pressure and now I know about 7 or 8 different drugs that you can use to treat it. But until I had people come back and tell me about these symptoms, I didn’t understand what was going on with them, and that’s how we figured it out. You have to listen to the patients.

Linda Gray-Leithe, MD is an Associate Professor of Neuroradiology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. She and her colleagues focus much of their clinical and research effort on refining diagnostic imaging and spinal intervention procedures for the treatment of intracranial hypotension due to spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. She has authored over 100 publications and book chapters with 25 publications focused on the area of CSF pressure abnormalities. She is also a member of the Medical Advisory Board of Spinal CSF Leak Foundation.