It’s not uncommon for patients to encounter misdiagnoses and delays before finding a proper diagnosis and effective treatment for spontaneous intracranial hypotension due to a spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. When Emma became ill at age 11, it took finding a specialist far from home to provide long-lasting relief. Now, twelve years later, Emma shares her story.

Emma was just 11 years old when she woke up one morning with a minor headache. She didn’t take much notice of it. An active kid and gifted athlete, she was always in motion, competing in multiple sports, running at top speed to get anywhere she needed to go. The night before, she’d had a pretty intense soccer practice. Perhaps her headache was from that? Her mother Amberly, a pharmacist and a perennial fan of all of Emma’s athletic endeavors, gave her some ibuprofen and sent her off to school.

Emma walked to school, like always, and joined the rest of her fifth-grade class in the gym as they waited for school to start. But something wasn’t right. Emma’s head pain was getting worse, not better. It felt like a constant pounding in her brain. When the bell rang to signal the beginning of the school day, Emma headed not to her fifth-grade classroom, but to the nurse’s office. Before she could make it there, the pain became too much. She slumped to the floor, unable to move.

The search begins

When the school called to say that Emma was ill and needed to be picked up, Amberly didn’t quite understand. “We live so close, can’t you just walk home?” she asked Emma, once the school nurse handed over the phone. “And Emma said, ‘No, mom. I can’t walk.’ And that was the first indication I had that there was something really wrong here.”

Emma’s local physician couldn’t find a reason for her symptoms and gave her a provisional diagnosis of migraine. She was sent home with migraine medication, which didn’t help her pain. In fact, she noticed, nothing seemed to help the pain—except for lying down. (A hallmark of the head pain experienced by people with spinal CSF leak is that it responds poorly to migraine medications. Read more about migraine and other misdiagnoses here.)

After a week of being flat with only brief periods of upright time, Amberly took Emma to a nearby hospital. The MRI she had there, without contrast, revealed nothing. Again, Emma was evaluated for migraine, despite her symptoms not responding to the migraine medication she’d already been given. Emma’s family physician was flummoxed; he told the family that what Emma was experiencing was outside the scope of his practice.

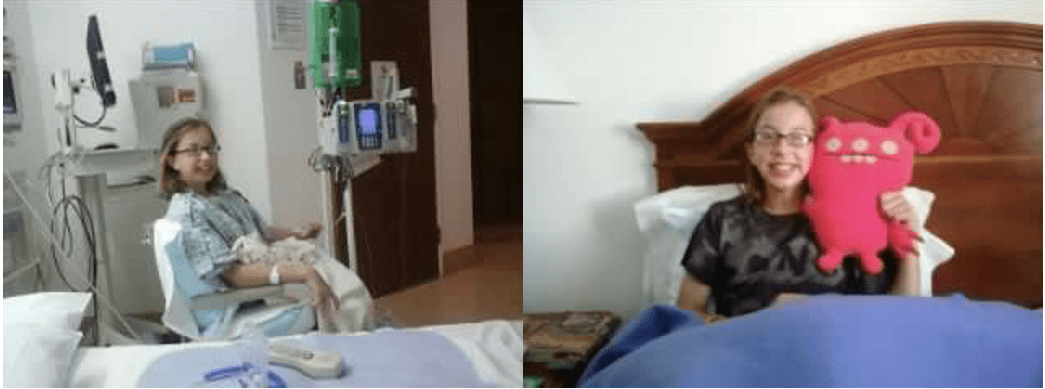

Emma returned to the hospital for more tests—a spinal MRI with contrast, which revealed nothing; a spinal tap, which also shed no light on what the cause could be. Emma was sent to a different children’s hospital, where she was admitted for 10 days of bed rest, IV fluids, and caffeine. But still, whenever she was upright, the head pain returned.

Clues revealed

Finally, Emma had another MRI, this one a brain MRI with contrast. And that scan indicated evidence of spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) due to a spinal CSF leak.

The brain and spinal cord are bathed in fluid known as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This fluid is held inside layers of connective tissue called the meninges, which surround the brain and spinal cord. The outermost of these layers is the dura mater, normally a tough connective tissue. A spinal CSF leak happens when the spinal dura mater has a hole or tear, allowing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to leak out of this enclosed space. This results in intracranial hypotension, a low volume of CSF remaining around the brain and spinal cord.

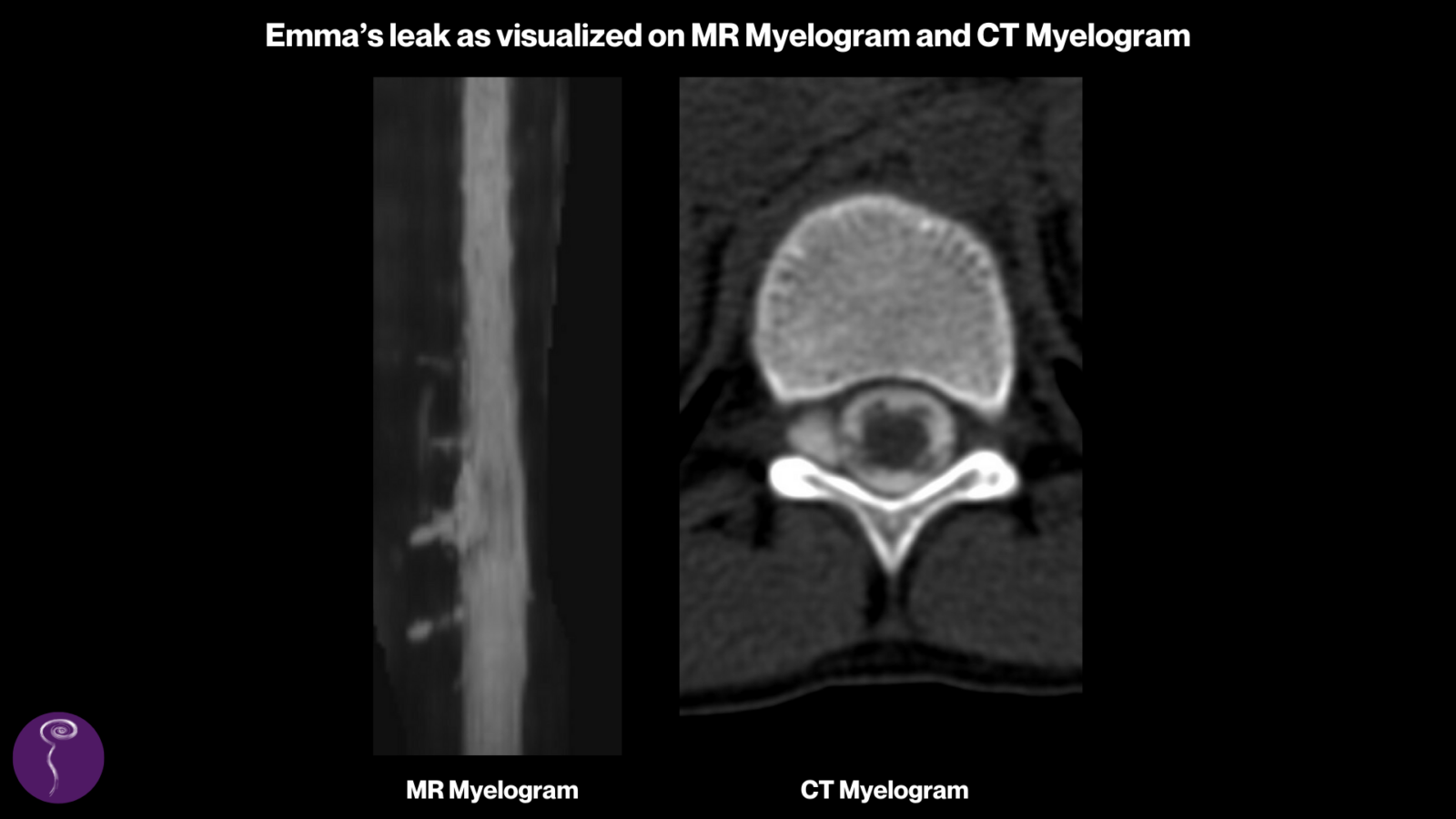

There are five findings typically seen on imaging that can be remembered by the mnemonic “SEEPS” when considering the diagnosis of spinal CSF leak. SEEPS stands for: Subdural fluid collections, Enhancement of pachymeninges, Engorgement of venous structures, Pituitary hyperemia, and Sagging of the brain. However, it is important to note that the absence of these findings does not rule out a spinal CSF leak. (Read more about spinal CSF leak diagnosis here.)

A way forward, and a step back

The doctors correctly surmised there was a leak somewhere along Emma’s spine and recommended an epidural blood patch. But because she was just 11, the physicians were loath to do it, as they had no experience in administering a patch to someone so young. (Read more here about blood patching and other spinal CSF leak treatment.)

Eventually, Amberly found someone willing to give Emma a blood patch, despite her age.

“After that first blood patch, it was like I was a normal kid again,” Emma said. She felt so good so quickly that she threw herself back into her favorite activities: playing basketball, running with friends, basically being the incredibly active kid she’d always been. And then, 72 hours after her patch, the head pain returned, pounding in her skull.

Amberly continued to look online for possible treatments and spinal CSF leak specialists who had experience with children.

“It was quite daunting. As a mother, I just felt immobilized. I felt like I would have given her or done anything to have gotten her to effective treatment,” she said. “When you’re staying with your child and they’re lying flat one month, two months . . . it’s a very long time. It was just a most helpless feeling.”

Treatment, and tentative success

Amberly finally found a specialist, far from their home in Dallas, and contacted him, leaving a detailed message about Emma’s experience. He called them back at nearly 11pm that same night and told them he could see Emma right away.

They packed their bags and headed to the specialist center immediately. Once there, Emma underwent more diagnostic imaging, which revealed a benign cyst on her spine from T11 to L2 that was leaking cerebrospinal fluid. (Find out more about different types of spontaneous spinal CSF leaks here.)

The specialist suggested doing a blood and fibrin glue patch in that area, or, alternatively, performing a more invasive surgical procedure. Emma opted for the patch. Afterward, the relief was immediate: Emma had no head pain or any of the other worrying symptoms she’d been battling for weeks. She and her mom were optimistic and relieved, and after a week and a half, they went back home. But just three days after their return, Emma’s symptoms returned as well.

They went back to the specialist, who offered to repeat the patch procedure. But Emma told him no: she wanted him to do the surgery. “My mom didn’t want me to have such an invasive surgery,” Emma said. “But in my head the entire time I was like no, it didn’t work the first time, we need to do more.”

Finally, relief

Emma underwent the three-hour surgery and woke up to discover she had a titanium clip in her back, clamping off the cyst—and no more headache. She and her mother stayed a bit longer in the area this time, just to make sure everything was okay, and Emma had follow-up MRIs to confirm that her cerebrospinal fluid was building back up and that the clip was doing its job. Once they had the all-clear, they returned home, and Emma has been headache-free ever since.

“I didn’t have any rebound high pressure, which was really odd, because they really thought that was going to happen,” Emma said. “The only head pain I had afterward was just your typical little headaches, the kind that go away with ibuprofen.”

One of the most frustrating things for Emma about her experience with spinal CSF leak was not being able to be active and participate in sports. “I’d hear kids running down the neighborhood, and normally if I heard them, I was out the door joining in. So that was hard.” When thinking about that time in her life, she remembers how she coped with those frustrating months of bed rest: “Sometimes my teammates would come over and we would play Mario Kart, or they’d show me videos of the soccer games they’d played without me. I think that was just the best way I coped with it. Because when you’re an 11 year old, you don’t think about it much. I mean, you’re just a kid. So you don’t know much about depression, or you don’t know much about anxiety. You just find toys or video games to keep you busy and you just cope with it.”

A future of helping others

It was also hard for her to see her mom so frustrated by the lack of answers they found while Emma was so ill. The doctors they saw seemed to be impatient with being unable to fix Emma or improve her symptoms, and Emma took this all in. Ultimately, she says the experience made her want to go into healthcare herself. She comes from a family of nurses and pharmacists and speech therapists, but the experience she had of being treated by so many different kinds of doctors at so many different hospitals gave her a unique perspective.

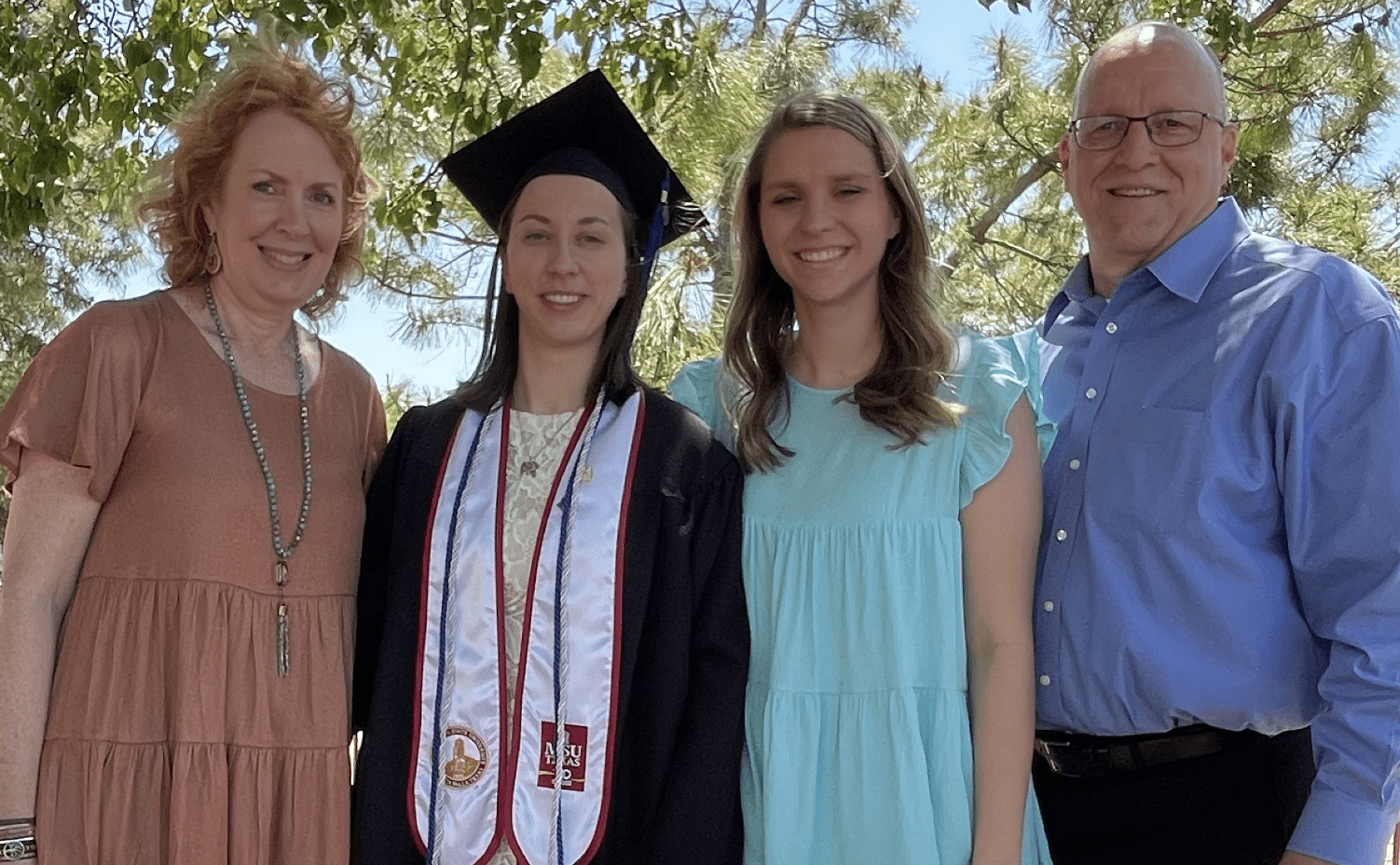

Twelve years after that morning when she woke up with a headache, Emma is a college graduate and certified respiratory therapist. She plans to become a registered respiratory therapist and is about to start a new job where she’ll be receiving training in an ER/ICU setting. Eventually, she’d like to be a helicopter transport therapist. “I just love it,” she says, of working in healthcare now. “I like being in the hospital, and most of all I love being able to help.”

The team at Spinal CSF Leak Foundation extends our appreciation and thanks to the family, physicians, and staff who assisted with this feature story, and to all those working so hard to help patients and raise awareness.