Spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak is an under-diagnosed cause of disabling daily headache with other neurological symptoms and complications that can happen to anyone. The underlying problem is a hole or tear of the dura mater, the tough layer that normally holds the CSF in around the brain and spinal cord. A spinal CSF leak is treatable, BUT ONLY if the correct diagnosis is made. Our tagline, because your dura maters®, highlights the TREATABLE aspect of this often very disabling neurological disorder.

Because spinal CSF leak is unfamiliar to most physicians, it is often misdiagnosed. Patients can suffer for months, years, or even decades with the wrong diagnosis and the wrong treatments. Medications rarely help. The most common symptom of head pain is often much worse after minutes to hours of being upright, so patients may have difficulty functioning for long while upright. The degree of disability can range from mild to profound.

Our primary goal of Leak Week is to raise awareness so that more patients might be correctly diagnosed and treated. We interviewed Dr. Wouter Schievink of Cedars-Sinai to teach us more about the dura mater, about spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and intracranial hypotension.

We know that the dura mater is a tough layer around the brain and spinal cord that holds fluid in and that a hole or tear of the dura mater allows this fluid to leak out. Would you share information with us that could allow us to better understand what the normal dura mater looks like in the operating room?

The dura is really a very beautiful smooth and glistening membrane that covers the spinal cord and the brain and the spinal fluid around it. It is actually a very tough membrane. The name is “dura mater,” which means “tough mother,” and it is somewhat similar to leather in that you cannot physically tear the dura mater apart. A very important membrane.

There are different causes of spinal CSF leaks and different types of CSF leaks. Can you tell us more about that, and about what you see with different types of leaks?

As far as the different causes of spinal CSF leaks, there are three groups: The traumatic leaks, the ones from medical procedures, and the spontaneous CSF leaks. Although about one out of three patients with spontaneous CSF leaks will report some sort of more or less trivial event that preceded the onset of the symptoms, when we talk about a spontaneous CSF leak we are really talking about those that are not caused by obvious trauma like stab wounds or gunshot wounds, or by a medical procedure such as a spinal tap or placement of an epidural catheter, spine surgery. Note that about 5% of spine surgeries are complicated by CSF leaks.

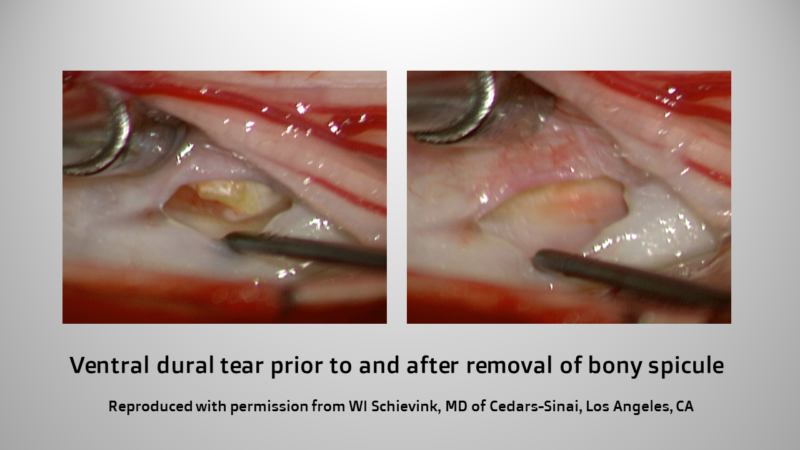

As far as the different types of spontaneous spinal CSF leaks, we really differentiate into three types. Type 1 is an actual tear or hole in the dura mater in the spine. Often times these are leaks that can have fairly dramatic onset in that the headache can come on very suddenly, which can mimic a brain hemorrhage. About 80-90% of these leaks are associated with a bony spicule [or bone spur] that has been rubbing against the dura and causes a hole in the dura. We have known about this since last century but we did not really know how common that was. Probably the reason is that a lot of these bony spicules are quite small ,so we are not really talking about large calcified herniated discs; it can really be just a speck of calcium. Most of these type 1 leaks are in front of the spinal cord but some are on the side or behind the spinal cord. These type 1 leaks are often difficult to treat when they are in front of the spinal cord. Generally, that is not where blood patches or glue injections have a very high success rate of actually fixing the hole.

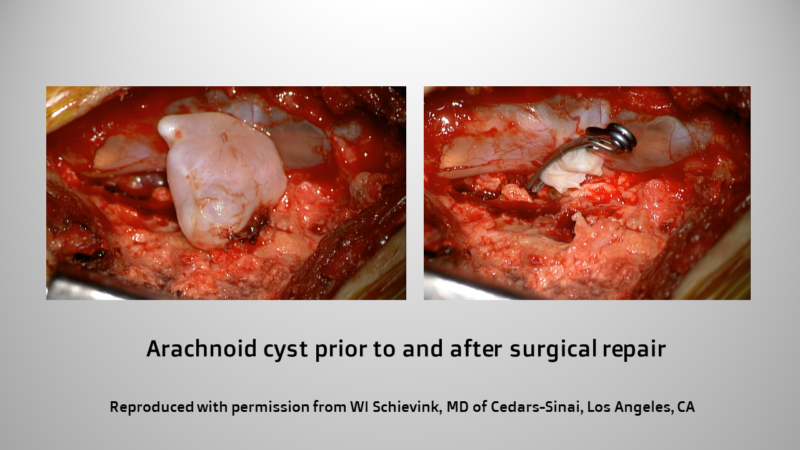

The type 2 leaks are a little bit more common, and these are associated with cysts. Cysts are fluid-filled cavities in the body, and the cysts that we are talking about in type 2 leaks are congenital cysts, meaning that people are born with them. They rarely get larger and if they do get larger in life, that really only happens in the first 10-15 years of life. Even in children, it is rare for these to get any larger. What we would formerly call a cyst of the spine, now actually really seems to be more a tear along the side of the dura. The lining under the dura can sort of billow out and look like a cyst, really the primary cause is a tear of the dura along the side of the spinal cord. We differentiate type 2 leaks into type 2a, which are more a common type of arachnoid cysts, and type 2b cysts, which are really very diffuse cysts that we sometimes call dural ectasia or very complex cysts due to the very abnormal dura. The entire dura often looks very abnormal. We can see that with different types of heritable disorders of connective tissue, particularly Marfan syndrome. We think that some of these people—even though they have the typical manifestations of CSF leaking in that they get a headache when they get up and the headache improves when the patient lies down, and they get brain sagging on their brain MRI—I think some of these people don’t actually leak spinal fluid but the fluid pools in the large dilated sac often at the bottom of the spine.

The type 3 leaks are a type of spinal fluid leaks that we have only known about for the last few years. This is a type of leak that we call a CSF-venous fistula. This is an abnormal and direct communication between a spinal fluid space and a spinal vein. Often times this spinal fluid space is one of these arachnoid cysts but not necessarily so. The spinal fluid space can just be the common dural sac and it is not related to a cyst at all. In surgery, these venous channels are much larger than the normal venous channels that everybody has in their spine that absorb spinal fluid. These venous channels can measure up to about 2 mm.

Can you explain how spinal injection procedures work? We are aware that both non-targeted and targeted approaches are used.

We don’t really know how epidural blood patches work. We know that when a person has a spinal tap and inadvertently a blood vessel is injured by the needle, which we call a bloody tap, we know from experience that people who have a bloody tap are less likely to get a headache after a spinal tap. Back in the 1950’s, there was a patient who actually had a spontaneous spinal CSF leak and her physician placed a blood patch with only half a milliliter of blood and that cured the patient’s symptoms of orthostatic [positional] headache. It is difficult to understand how half a milliliter of blood would be able to cure that by causing a little scab on the dura, but what we usually tell our patients, and what we usually tell ourselves and our colleagues that that is how a blood patch works. It works because there is a scab that covers up the tear. But probably that happens in a small minority of patients. In the vast majority of patients who have epidural blood patches because of a spinal CSF leak, most people feel better right away because you actually inject blood into the spinal canal, which will cause an immediate increase of spinal fluid pressure. As the blood clot gets absorbed, the blood patch causes scarring and inflammation in the space around the dura, the epidural space. Any spinal fluid that leaks into the epidural space just doesn’t have anywhere to go anymore, so this allows the body to heal the little hole just by itself.

In addition to blood patches, we have also been treating patients with injections of glue. In the past, up until around the year 2000, when blood patches did not work, people would go to surgery. We started injecting glue where we thought the leak was coming from. The glue works a little bit differently than blood patches, in that to use glue, we really need to have a target. With blood patches, we really do not need to know where the leak is. When doing a blood patch in the lower part of the spine, the lumbar spine area, it has a really high likelihood of fixing the leak. When blood patches don’t work and there is a target for glue, the glue works by sealing the leak. That allows the body to make a little scar tissue over that hole. The glue really only lasts for 3 or 4 weeks and then it is gone, and the glue properties of glue actually disappear within 2 or 3 days.

The experience for the patient is similar for blood patches and glue; they are both outpatient procedures. With blood patches, we really feel, and other people have demonstrated, that higher volumes of blood have a higher chance of successful outcome, so for blood patches we try to inject a lot of blood without causing any injury, so for the part where the blood is injected, the patient needs to be awake to tell us what they are experiencing. For glue, that is not so much of an issue because for glue it is not necessary to inject a large volume. We just need to be very precise about the location. For the glue injection, the patient is not really awake. They are usually given some intravenous sedation.

Can you tell us a bit about how you repair the different types of leaks in the operating room when that is needed?

There are different ways of securing a spinal fluid leak, and often times we don’t really know until I actually see what the leak looks like under the surgical microscope.

For the type 1 leaks, those caused by dural tears usually related to a piece of bone, we almost always approach those leaks, even though they are in front of the spinal cord, from the back. We find the hole by going around the spinal cord, and then if the hole or tear is not right in the middle behind the spinal cord, we usually use small sutures to close that hole. If the dura is really weak and certainly if the hole is right in the middle in front of the spinal cord, which makes suturing risky, then I use a little muscle graft to close the hole. The success rate of both of those procedures, sutures or a muscle graft, are essentially identical.

For the type 2 leaks, leaks that are associated with arachnoid cysts along the spine, I like to use small titanium clips that we use for aneurysm surgery. That has been shown to be very effective. Sometimes if the dura is a really good quality, I might suture the hole in the cyst. Sometimes, again, I use a little muscle graft. Sometimes, to secure the cyst or if we are talking about dural ectasia, I coat the dura with an artificial dural graft that will seal to the patient’s own dura over a time period of about a month or so.

For the type 3 leaks, the CSF-venous fistula, you can use very small titanium clips to interrupt that fistula or you can just use small electrocautery to obliterate the venous channel.

Can you share with us some of your thoughts about WHY this diagnosis is often missed or delayed?

I really think that the number 1, 2, and 3 reasons for that is just persistent unfamiliarity with the syndrome of spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Although this is not that common, it is certainly not very rare either. There are many different reasons why the diagnosis can be a bit more difficult. Many people with a spontaneous leak, like a leak after a spinal tap, the typical manifestation is a headache that is obviously orthostatic [positional]. If that is the case, more so now as compared with 5 or 10 years ago, the diagnosis IS often made in a day or two without any type of imaging by family doctors, neurologists, or neurology residents. But if their headache lingers, it may not be so orthostatic [positional] anymore. If, in the beginning, a spinal tap was done, then the orthostatic headache might be attributed to the initial spinal tap. The symptom of neck pain is a common but non-specific symptom. If a brain MRI is done and it is normal, patients will often be told that they do not have a spinal fluid leak. We don’t know exactly how common normal brain MRIs are, but in our practice, about 1 in 5 patients always have a normal brain MRI, even though there is a documented spinal CSF leak. It could be that the percentage with normal brain MRI in the general population of spinal fluid leak patients is much higher because a lot of patients will not be diagnosed and will not be seen in our office.

You and your colleagues at Cedars-Sinai see a lot of patients with intracranial hypotension. Do you have any sense or research on what percentage of patients are misdiagnosed before they come to Cedars-Sinai?

When we first looked into this, about 15 years ago, greater than 95% of patients were initially misdiagnosed, and even though we have not looked at this recently, my feeling is that the initial misdiagnosis is still extremely common, I would say, over 90%. I do think that the delay to correct diagnosis has been cut significantly. We will be looking at this again in a more scientific fashion in the next year or two.

What are some of the incorrect diagnoses you see?

The vast majority of patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension present with a headache. The most common incorrect diagnoses are the two most common causes of headache, which are tension headache and migraine headache. Another fairly common misdiagnosis is sinusitis. Viral meningitis might be diagnosed when a spinal tap shows some white blood cells in the CSF, which is also common in a spinal CSF leak. Patients who have a sudden onset of severe headache and a spinal tap is done, and if there is some blood in the spinal fluid, they might be diagnosed with a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Conversely, patients who have had their leak ongoing for months, years or even decades, they can often be diagnosed with malingering or if is a child, they might be diagnosed as Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Those are very persistent and common misdiagnoses.

What are some of the more common complications that you see?

In addition to headache, a lot of patients have other symptoms or complications from their leak. The most common other symptoms are neck pain, hearing loss, ringing in the ears, tremors, disequilibrium.

Common complications that can be seen on a scan, particularly on MRI but also on CT, are subdural fluid collections or hematomas [blood clot pressing on the brain] which occur in 20% of patients. These patients will usually be seen by neurosurgeons who typically will operate on these if the subdural hematoma is large enough. If the underlying leak is not recognized or fixed, there is a high likelihood that the subdural hematoma will recur, and there is a chance that the patient will get worse after the removal of the subdural hematoma.

Another common complication seen on brain MRI is sagging of the brain. If the radiologist or the treating physician is not familiar with it and if the sagging also includes the back part of the brain, it looks like a Chiari malformation. This resolves when you fix the spinal CSF leak. {READ MORE ABOUT CHIARI MALFORMATION HERE]

What are some of the less common complications that you see?

There are certainly complications that now we know are caused by spontaneous CSF leaks in the spine, but that 10 or 20 years ago we did not know about. Of these less common complications, probably coma is the most important because it is something that is life-threatening. We do see it on a regular basis. It can be very dramatic in that within 15-30 minutes of repositioning with the head down, the patient will wake up.

Another devastating complication is something called fronto-temporal dementia, in which a patient in their 30’s, 40’s or 50’s, often confined to a nursing home, has very dramatic cognitive disabilities and personality change, but the cause is a spinal fluid leak. The majority of these patients can be cured of their dementia.

Another complication is called superficial siderosis, which is when the brain and spinal cord is coated with iron deposits from a small amount of chronic bleeding. These patients usually have hearing loss and difficulty with walking.

More rare is bibrachial amyotrophy, in which patients come in with atrophy and weakness of the muscles of the shoulders and arms. This can look like ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).

Occasionally when a patient has a tear in the dura mater in front of the spinal cord, the spinal cord can poke thru the hole in the dura. These patients might have paraplegia or paraparesis, where they lose strength or sensation in their lower extremities.

Can you explain how CSF leaks in the head (cranial leaks) differ from CSF leaks in the spine?

One of the more important differences are that when there is a CSF leak in the head, these are people that leak CSF thru the nose mainly, or from the ears. This is dangerous in that there is a risk of meningitis. With a leak in the spine, there is no communication with the outside environment, so this risk is not present.

The second very important difference is that people that leak CSF from their nose or ear do not get headaches or spontaneous intracranial hypotension. This is a VERY common misconception. For a positional headache to occur or typical brain imaging changes to occur, it is necessary to look for a CSF leak in the spine. It is important to note that headaches due to spinal CSF leak and headache due to migraine are often accompanied by some excess clear nasal drainage which is just a reaction to the pain; it is not CSF.

How do you approach a patient in whom a leak is suspected but does not show up on imaging?

I think it is really important to emphasize that even in people that we know must have a spinal CSF leak because their brain MRI shows sagging of the brain and they have the typical enhancement of the dura after administration of IV contrast, we can only find the leak in about 50%. So if I suspect a leak and we do see typical changes on the brain MRI but we do not see a leak on spinal imaging, this is a very common scenario, and we just go ahead and treat that patient with patching.

It is a bit more difficult if all imaging is normal; if the brain imaging is normal and the spine imaging is normal. There are different ways of approaching this. For example, if a patient has a typical positional headache and the brain MRI is normal, spine MRI is normal, and I don’t have a high index of suspicion for another reason for their positional headache, we often go ahead and perform an epidural blood patch. The number one reason to do this is to try to cure the headache, but the other reason is to use it as a test. If the patient does really well with the blood patch, but after 2 months the headaches comes back, then we will go ahead and repeat the blood patch. Now, if we feel that it needs to be investigated more thoroughly because it is not really that clear that the symptoms are caused by a leak, or if the patient does not really have a good result from a blood patch, then we might proceed with more invasive types of spine imaging in order to identify a leak.

We also may do an intrathecal saline infusion, in which a patient is admitted to the hospital for a few days, and through a spinal catheter, we infuse artificial CSF to see if that alleviates the symptoms. We might also repeat spinal imaging after the infusion.

What fraction of patients that you see are cured?

Of the patients that we have seen at Cedars-Sinai with a confirmed leak, about 80% are cured. Of course, there is an unknown fraction of patients in whom symptoms resolve spontaneously as well as many who never reach us for care. So the overall rate of resolution is probably higher. We will need to study this as more patients are diagnosed.

While we understand that most patients do well, not all patients are improved or cured in a short time frame. What do you see as the top research priorities that may improve outcomes for more patients?

I think that we need to improve our diagnostic testing. We need to be better able to identify the location of a spinal fluid leak, even though it is really only important for a minority of patients, it remains a very important research priority. Also, we might be able to develop a blood test that can show that a person has a spinal CSF leak.

We could develop models of spinal CSF leak, which could be a biomechanical model, or a mathematical model, or an animal model. This could help to investigate treatments for leaks, or methods to improve the strength and durability of the dura mater.

Do you have any additional thoughts that you would like to share?

The number one priority to improve outcomes for patients is to get the word out. That is why this Spinal CSF Leak Awareness week is so important.

Wouter I. Schievink, MD is a Professor of Neurosurgery, Director of the Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak Program and Director of the Vascular Neurosurgery Program at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles. He has published extensively on intracranial hypotension due to spinal cerebrospinal fluid leak. He is also a Medical Advisory Board member of Spinal CSF Leak Foundation.